CAPOEIRA

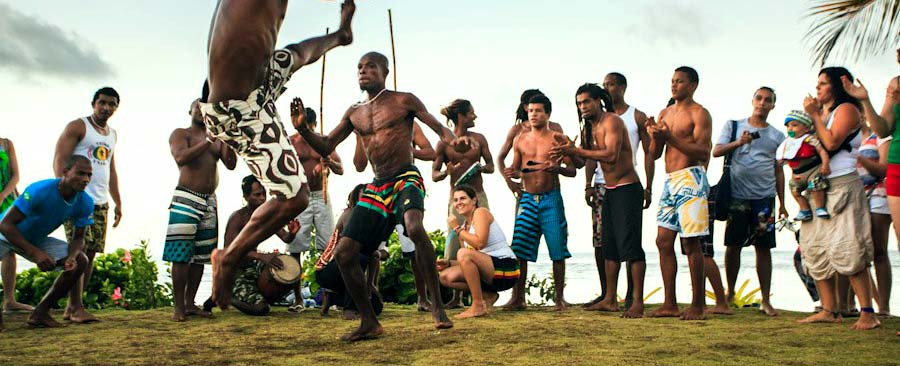

Itacaré, with its highly skilled capoeirists and perfect environment, is certainly one of the best places in the world to practise capoeira.

Capoeira is a combination of dance and fight, mixing martial art moves with music. It is impressive not only due to the physical strength of those who participate, but also due to the remarkable display of flexibility and delicacy that the capoeirists demonstrate in their movements.

Capoeira is a combination of dance and fight, mixing martial art moves with music. It is impressive not only due to the physical strength of those who participate, but also due to the remarkable display of flexibility and delicacy that the capoeirists demonstrate in their movements.

The musical instruments used to accompany the capoeiristas are essential to capoeira. The berimbau instrument is the most important; it determines the rhythm of the fight by strumming or striking the instrument in different ways, each with its own purpose. But capoeira is not accompanied by the berimbau alone. Besides the berimbau the following instruments are used: atabaque, pandeiro (tambourine), reco-reco and caxixi...

In Itacaré it's not possible to talk about capoeira without mentioning Master Jamaica. Founder of the first capoeira group in Itacaré, he was greatly responsible for the growth of this art here.

In Itacaré it's not possible to talk about capoeira without mentioning Master Jamaica. Founder of the first capoeira group in Itacaré, he was greatly responsible for the growth of this art here.

THE GROUPS OF ITACARÉ

Now there are three main capoeira groups in Itacaré: Filhos de Zumbi, Tribo Bahia and Tribo do Porto.

They all practise Regional Capoeira and organize daily training, frequented by many children and young people - fulfilling an important social role in the community - and always open to visitors for classes.

THE HISTORY OF CAPOEIRA

In the 1500's the Portuguese, led by explorer Pedro Alves Cabral, arrived to Brazil. One of the first measures taken by the new arrivals was the subjugation of the local population, the Brazilian Indians, in order to provide the Portuguese with slave labor (for sugarcane and cotton).

Attempting to enslave these Indians was a failure. The Indians quickly died in captivity or fled to their nearby homes. The Portuguese then began to import slave labor from Africa (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form). On the other side of the Atlantic, African free men and women were captured, loaded onto ghastly slave ships and sent on nightmarish voyages that for most would end in perpetual bondage.

The Africans first arrived by the hundreds and later by the thousands (approximately four million in total). Three major African groups contributed in large numbers to the slave population in Brazil; the Sudanese groups who were composed largely of Yoruba and Dahomean people, the Mohammedanized Guinea-Sudanese groups of Malesian and Hausa people and the "Bantu" groups (among them Kongos, Kimbundas and Kasanjes) from Angola, Congo and Mozambique (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

The Bantu groups are believed to have been responsible for the foundation and birth of capoeira. They brought their culture with them in body, mind, heart and soul. A culture that was transmitted from father to son throughout generations. There was 'candomble', their religion; the berimbau, a musical instrument; vatapa, a food; and so many other things. Basically they brought with them a way of life (Wagner Bueno, 1996, Audio Tape).

The Dutch controlled parts of the northeast between 1624 and 1654. They lashed out against the Portuguese colony, invading towns and plantations all along the northeast coast, concentrating on Recife and Salvador. With each Dutch invasion, the security of the plantations and towns were weakened. The slaves, taking advantage of these opportunities, made many attempted escapes from the Portuguese during this time in search of their freedom. After escaping they often founded independent villages called quilombos (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

The quilombos were very important to the evolution of capoeira. There were at least ten major quilombos with internal socio-economic organizations and commercial relationships with neighboring cities. The quilombo 'Palmares' lasted sixty-seven years, located in the interior of the state of Alagoas. It survived almost all expeditions sent to destroy it (Wagner Bueno, 1996, Audio Tape).

Because of the constant threat of attacks, capoeira developed as a fight, or rather a self-defence mechanism in the quilombos. The roots of capoeira as a 'rudimentary fight' came from the original slaves' quarters and perhaps would not have developed further if left only to that environment.

Because of the constant threat of attacks, capoeira developed as a fight, or rather a self-defence mechanism in the quilombos. The roots of capoeira as a 'rudimentary fight' came from the original slaves' quarters and perhaps would not have developed further if left only to that environment.

As of 1814, capoeira and other forms of African cultural expression suffered repression and were prohibited in some places by the slave masters and overseers. Up until that date forms of African cultural expression were allowed and sometimes even encouraged, not only as agauge against internal pressures created by slavery but also to bring out the differences between various African groups, in a kind of "divide and conquer" way. But with the arrival of the Portuguese king Dom Joao VI in Brazil in 1808 (and his court), who were fleeing Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Portugal, things changed. The newcomers understood the necessity of destroying a people's culture in order to dominate them, and capoeira began to be persecuted in the process, which would culminate with it being completely outlawed in 1892.

Why was capoeira suppressed? There were many motives. First of all the Portuguese believed it gave Africans too much of a sense of pride and unity. It also developed self-confidence in individual capoeiristas. Capoeira created small, cohesive groups. It created dangerous and agile fighters. Sometimes the slaves would injure themselves during capoeira, which was also not desirable from an economical point of view (Wagner Bueno, 1996, Audio Tape). The masters and overseers were probably not as conscious as the king and the intellectuals of his court of all of these motives, but intuitively they must have known that something wasn't quite right and that it should be stopped.

It must be stressed that there are many other theories attempting to explain the origins of capoeira. According to one prevalent theory, capoeira was a fight that was disguised as a dance so that it could be practised unbeknownst to the white slave owners. This seems unlikely because, around 1814 when African culture began to be repressed, other forms of African dancing suffered prohibition along with capoeira, so there would have been no sense in disguising capoeira as a dance (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

Another theory says that the Mucupes in the South of Angola had an initiation ritual (efundula) for when girls became women, on which occasion the young warriors engaged in the N'golo, or "dance of the zebras," a warrior's fight-dance. According to this theory, the N'golo was capoeira itself. This theory was presented by Camara Cascudo (Folclore do Brasil, 1967), but one year later Waldeloir Rego (Capoeira Angola, Editora Itapoan, Salvador, 1968) warned that this "strange theory" should be looked upon with reserve until it was properly proven (something that never happened). If the N'Golo did exist, it would seem that it was at best one of several dances that contributed to the creation of early capoeira (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

Other theories mix Zumbi, the legendary leader of the Quilombo Palmares (one of the communities of escaped slaves) with the origins of capoeira, without any reliable information on the matter (Bira Almeida, 1986 Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

All of these theories are extremely important when we try to understand the myth that surrounds capoeira, but they clearly cannot be accepted as historical fact according to the data and information that we presently have. Perhaps with further research, the theory that we have proposed here, i.e. capoeira as a mix of various African dances and fights that occurred in Brazil, primarily in the 19th century, will also be outdated in future years (Bira Almeida, 1986, Capoeira - A Brazilian Art Form).

With the signing of the Golden Law in 1888, which abolished slavery, the newly freed slaves did not find a place for themselves within the existing socio-economic order. The capoeirista with his fighting skills, self-confidence and individuality, quickly descended into criminality and capoeira descended along with him. In Rio de Janiero, where capoeira had developed exclusively as a form of fighting, criminal gangs were created that terrorized the population. Soon thereafter, during the transition from the Brazilian Empire to the Brazilian Republic in 1890, these gangs were used by both monarchists and republicans to exert pressure on and break up the rallies of their adversaries. The club, the dagger and the switchblade were used to accompany the various capoeira moves (Wagner Bueno, 1996, Audio Tape).

In Bahia on the other hand, capoeira continued to develop into a ritual-dance-fight-game, and the berimbau began to be an indispensable instrument used to lead the rodas (sessions of capoeira demonstrations), which always took place in hidden places since the practise of capoeira in this era had already been outlawed by the first constitution of the Brazilian Republic (1892).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in Rio, the capoeirista was a criminal. Whether the capoeirista was white, black or mulato (mixed), he was an expert in the use of kicks (golpes), sweeps (rasteiras) and head-butts (cabecadas), as well as in the use of blade weapons. In Recife capoeira became associated with the city's principal music bands. During carnival time tough capoeira fighters would lead the bands through the streets of Recife, and whenever two bands met, fighting and bloodshed would usually ensue. In Bahia the capoeirista was also often seen as a criminal (Wagner Bueno, 1996, Audio Tape).

The persecution and the confrontations with the police continued. The art form was slowly wiped out in Rio and Recife, leaving capoeira only in Bahia. It was during this period that legendary figures and respected capoeiristas such as Besouro Cordao-de-Ouro in Bahia, Nascimento Grande in Recife and Manduca da Praia in Rio, who are celebrated to this day in capoeira, made their appearances. It is said that Besouro was the teacher of another famous capoeirista by the name of Cobrinha Verde. Besouro did not like the police and was known not only as a capoeirista but also for having his corpo fechado (a person who through specific magic rituals supposedly attains almost complete invincibility in the face of various weapons). An ambush was set against him, but apparently Besouro (who could not read) carried a written message identifying himself as the person to be killed, thinking that this was a message that would bring him work. Legend says he was killed with a special wooden dagger prepared during magic rituals in order to overcome his corpo fechado (Nestor Capoeira, 1995, The Little Capoeira Book)

Of all those who led the carnival bands through the streets of Recife, Nascimiento Grande was one of the most feared. Some say he was killed during police persecution in the early 1900s, but others say he moved from Recife to Rio de Janeiro and died of old age there (Nestor Capoeira, 1995, The Little Capoeira Book).

Manduca da Praia was of an earlier generation (1890s) and always dressed in an extremely elegant style. It is said that he owned a fish store and lived comfortably. He was also one of those who controlled elections in the area he lived. It is said that he had twenty-seven criminal cases against him (for assault, knifing etc.) but was always let off due to the influence of the politicians he worked for (Nestor Capoeira, 1995, The Little Capoeira Book).

The two central figures of capoeira from the twentieth century were undoubtedly Mestre Bimba and Mestre Pastinha. These two figures are so important in the history of capoeira that they (and the mystery that surrounds them) are the mythical ancestors of all capoeiristas. Much of what a modern capoeirista tries to be comes from what these men were or what they represented.

In 1932 in Salvador, Mestre Bimba (Manuel dos Reis Machado) opened the first capoeira academy. He started teaching what he called "the regional fight from Bahia," which eventually became known as Capoeira Regional (faster and more aggressive than traditional Angola-style Capoeira). This feat was made possible by the nationalistic policies of Getulio Vargas, who wanted to promote capoeira as a Brazilian sport. Although Bimba opened his school in 1932, the official recognition only came about in 1937, when it was technically registered. It must be noted that the Getulio Vargas government permitted the practise of capoeira only in enclosed areas that were registered with the police (Nestor Capoeira, 1995, The Little Capoeira Book). With the opening of Bimba's Academy, a new era in the history of capoeira began, as the sport was now taught to children from the upper classes in Salvador. Bimba was active in capoeira his whole life. As a matter of fact he was planning to give a capoeira demonstration on the day he died, February 5, 1974.

In 1941, Mestre Pastinha (Vincente Ferreira Pastinha) opened his Capoeira Angola school. For the first time capoeira began to be taught and practised openly in a formal setting. He became known as the "Philosopher of Capoeira". Unfortunately government authorities closed down his academy, under the pretext of reforming the Largo do Pelourinho in the historical centre of Salvador.Although he was promised a new one, the government never came through (Nestor Capoeira, 1995, The Little Capoeira Book). The final years of his life were sad. Blind and almost completely abandoned he lived in a small room until his death in 1981 at the age of ninety-two.

Capoeira has grown tremendously over the last fifty years. It has finally been accepted by the masses in Brazil. Capoeira competitions and academies are surfacing everywhere. In 1974 it was recognized as the national sport of Brazil, which forced the creation of a National Federation of Capoeira. This was formed to govern, promote and coordinate capoeira. No effort had previously been made to unite the various types of capoeira throughout Brazil.

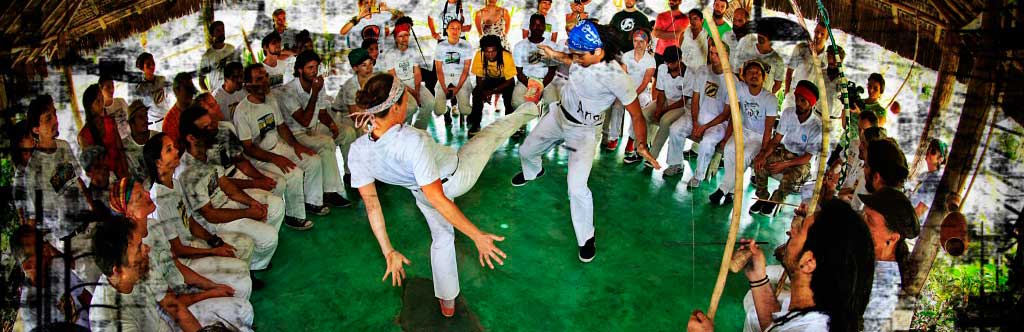

How is capoeira practised today? It usually starts with musicians playing instruments such as the berimbau (one string, bow type instrument), atabaque (congo), pandiero (tambourine), and agogo (bell). The musicians are based at the foot (pe' da) of the circle (roda).This roda is made up of participants (capoeiristas) crouching down. The musicians and-or capoeiristas may be singing a song in Portuguese. The participants enter the game from the pe'da roda (foot of the circle), usually with a cartwheel (au). Once in the circle the two players interact with a series of jumps, kicks, flips, hand and headstands and other ritualistic moves. Games can be friendly or competitive. The music plays a big part. The type of capoeira to be played (fast or slow, friendly or tough) depends upon the rhythm being played and the content of the lyrics being sung.

Capoeira has expanded beyond the borders of Brazil and is growing rapidly in other countries (including the United States). Capoeira appeals to many for many different reasons. First of all the pure beauty of the art is hypnotic. Capoeira is a dance and a fight. It's not only a combination of gymnastics, dance and martial arts but also music, culture, history and knowledge. The capoeirista must learn to balance the physical with the mental. The capoeirista must play many instruments and sing. The capoeirista may at times be your enemy but is usually a friend. The capoeirista is a historian. The capoeirista is all of these.

este site em Português

este site em Português este sitio en Español

este sitio en Español ce site en Français

ce site en Français